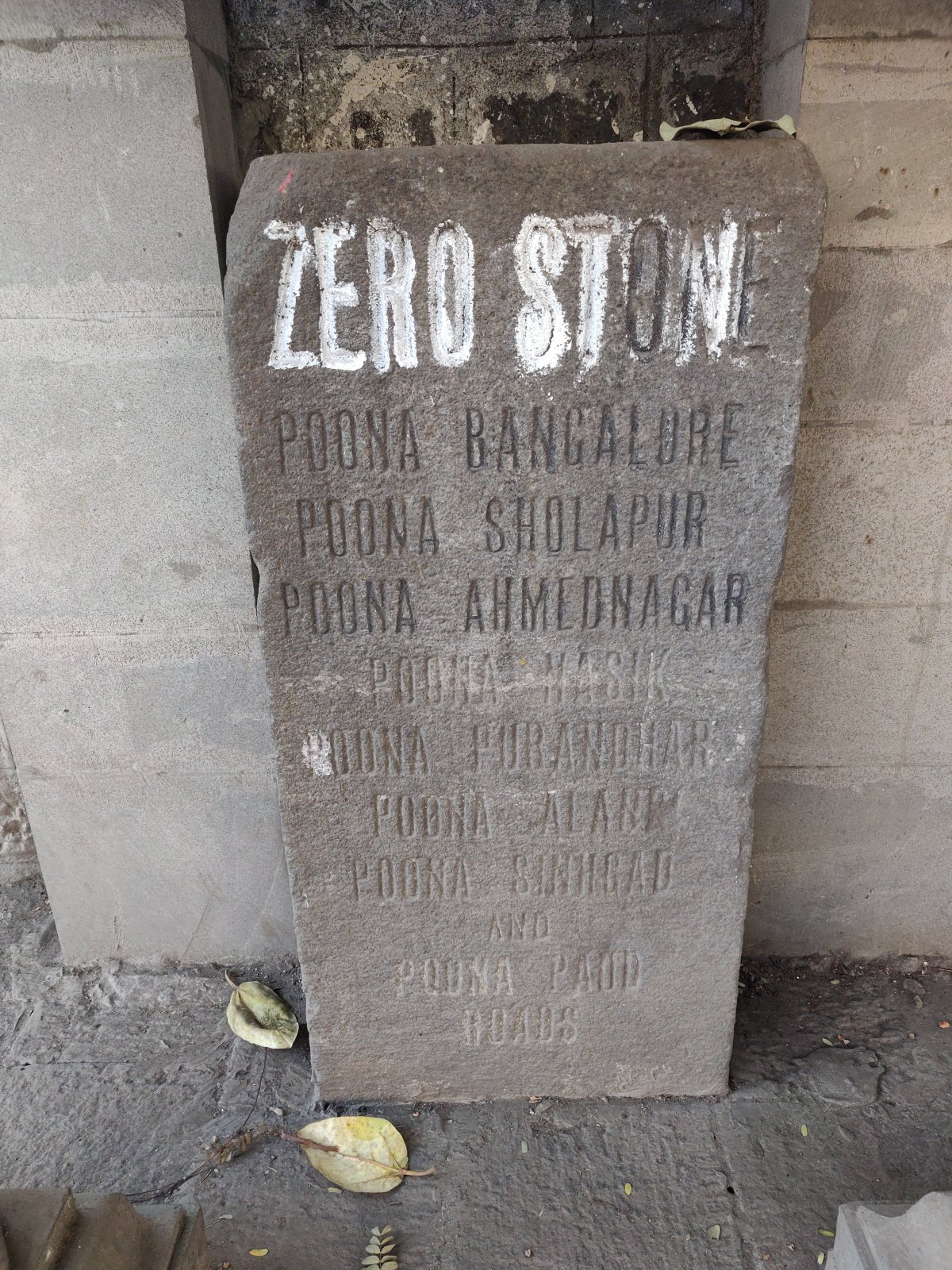

On a breezy evening in February 2019, I was just rounding up a special trip to Pune, looking to buy a postcard (yes, some of us still send them to loved ones). As I was returning from the Pune General Post Office empty-handed, I saw a relatively arcane object of interest, in the centre of a small arch made on a pavement adjacent to the post office. I thought to myself, “Wait… Is this it?” It was. It was a stone slab, about two-and-a-half-feet tall, with the words “Zero Stone” written on it. This was the stone which has officially marked the centre of Pune, the spot where all distances from Pune are measured from, since 1872, when it was installed here.

I returned to this exact spot a year later, to find that the stone, and its surroundings, looked completely different. But before that – let’s talk about zero mile markers in general.

Zero Points Around the World

Across the world, there exist particular locations (known as zero points, zero mile markers, control stations, or kilometre zero), from which distances are traditionally measured. Perhaps the most famous of these is the Milliarium Aureum (‘Golden Milestone’) that was erected in the centre of Rome around 20 BC by the Roman Emperor Augustus. This milestone is what all distances in Ancient Rome were measured relative to. It is believed that this is where the English saying, “All roads lead to Rome” comes from. Unfortunately, the stone has been lost, and we don’t know where it is, but there exist other such monuments around the world, built much later.

Crosses and Statues: The Zero Point of London

As I was reading about zero points across the world, I brushed up a little bit on the history of the zero point in London, which I had seen in various documentaries on the city. London is one of my favourite cities in the world, and since its mediaeval history has always fascinated me, I couldn’t help but include it in the article.

The history of the current zero point of London goes as far back as as the 1290s, to the death of queen consort Eleanor of Castile, the wife of King Edward I of England (also known as Edward Longshanks and the villain of the film Braveheart – whose historical inaccuracies haunt me to this day). Eleanor, born in the royal family of Castile in Spain, married Edward I in the year 1254 at the age of thirteen. She died in the year 1290, at the age of 49 in the village of Harby near Nottingham, while on a trip to Lincoln to meet her children.

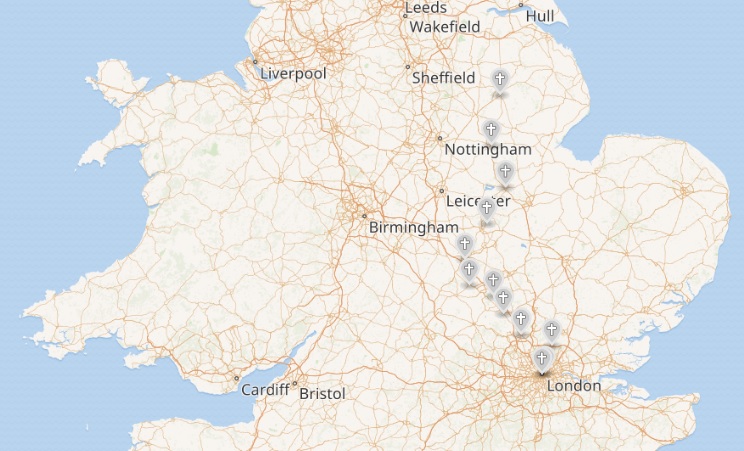

Eleanor’s body was embalmed, and carried from Lincoln to the royal capital of Westminster (which had then not been engulfed by London, a couple of miles to the east) to be buried at Westminster Abbey. The king gave orders for memorial crosses to be erected at the site of each overnight stop between Lincoln and Westminster. These crosses are known today as Eleanor Crosses, and their locations can be seen in the following map.

The tiny village of Charing, a mile north of Westminster, was the site of one of the last of Eleanor’s crosses, known as Charing Cross. With the installation of the cross here, the entire hamlet eventually came to be known as Charing Cross, today the site of a large station on the London Underground and National Rail networks.

Photo: Stephen McKay

The original cross was erected between the village of Charing and the entrance to the Royal Palace of Whitehall, today the south side of Trafalgar Square, where it stayed for about 350 years, before it was destroyed in 1647 during the English Civil War, on the orders of Oliver Cromwell, a Parliamentarian who subsequently declared himself as the ‘Lord Protector’ during a brief period of English history known as the Interregnum, when the monarchy was suspended.

Methinks the common-council shou’d

Of it have taken pity,

‘Cause, good old cross, it always stood

So firmly in the city.

Since crosses you so much disdain,

Faith, if I were you,

For fear the King should rule again,

I’d pull down Tiburn too.

An extract from ‘The Downfall of Charing Cross’, one of many English poems with this title, sourced from ‘Reliques of Ancient English Poetry’, Sixth edition, Volume 3, by Thomas Percy.

In 1660, the Interregnum came to an end, and Charles II, the son of Charles I (who was dethroned and killed by the Parliamentarians), was coronated as the King of England in 1661. Historians of Mumbai have much reason to study King Charles II (and his marriage to Catherine of Braganza), but that’s a story for another blog post. Anyway, after returning to the English throne, Charles II set about avenging the death of his father. Eight of those parliamentarians who signed the death warrant of Charles I were executed publicly near the spot of Eleanor’s Cross at Charing that was taken down, and an equestrian statue of King Charles I, that was made in 1633 before the English Civil War broke out and was hidden by the man charged with destroying it, resurfaced and was installed at the spot of the former cross in 1675. This statue has been used as the site from where all distances in London are measured since the early 1800s.

Photo: Tony Avon.

Photo: Diane Griffiths

The 1800s also saw the expansion of railways across the country. In 1864, a railway station was built at Charing Cross, and in 1865, in the forecourt of the railway station was erected a memorial to Eleanor of Castile – a fanciful reconstruction of the original mediaeval Charing Cross, designed by architect E. M. Barry, who based the monument’s design on the 3 surviving drawings of the original Charing Cross. It still stands today as the Queen Eleanor Memorial Cross.

Photo: Tony Hisgett.

Here is a map showing the exact site of the statue:

Measuring the Indian Subcontinent

Coming back to India, the year is 1800, and although most of modern-day India is still under the control of the Maratha Empire, the British East India Company is expanding rapidly. Having just defeated Tipu Sultan in a series of four Anglo-Mysore Wars, the Company now directly controls the southern and eastern parts of the country. The political map of India in 1800 looked something like this:

Source: The History of India, Every Year by OllieBye.

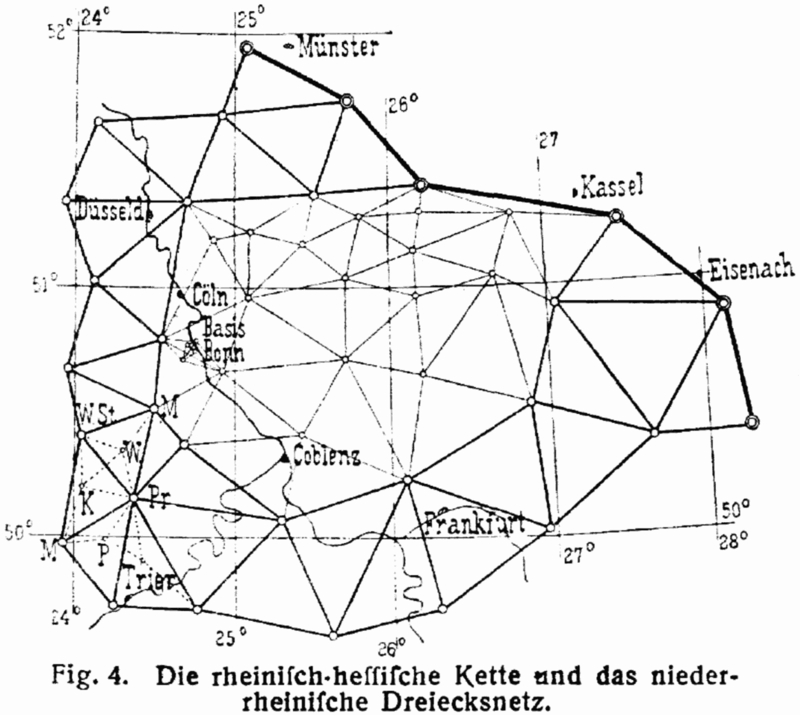

As the Company gained more territory, it employed several explorers and cartographers to provide maps and other information on its territories. However, over time it became known that there were many serious flaws that emerged in these maps due to a lack of precise measurements. In 1800, shortly after the Company’s victory over Tipu Sultan of Mysore, William Lambton, an infantry officer with experience in surveying proposed an alternative method of measurement – involving a series of triangulations, initially through the newly acquired territory of Mysore, and eventually across the entire subcontinent.

What is triangulation?

Triangulation is the process of determining the location or altitude of an unknown point by measuring angles to it from known points at either end of a fixed baseline, rather than measuring distances to the point directly. This remained the most efficient method to survey large areas of land until the 1980s with the advent of global navigation satellite systems.

Source: Wikipedia.

The Great Trigonometrical Survey of India

The Great Trigonometrical Survey of India was a project aimed to measure the entire Indian subcontinent with scientific precision. It was the first time that a survey of such scale and precision was carried out anywhere in the world. It was initiated in 1802 by William Lambton, under the auspices of the British East India Company, given its formal name in 1818, and was completed in 1871, having been chaired by George Everest (of Mount Everest fame), Andrew Scott Waugh and James Walker.

Among the many accomplishments of the Survey were the demarcation of British territories in India and the measurement of the height of several Himalayan peaks such as Mount Everest, K2 and Kanchenjunga. The Survey had an enormous scientific impact as well, being responsible for one of the first accurate measurements of a section of an arc of longitude.

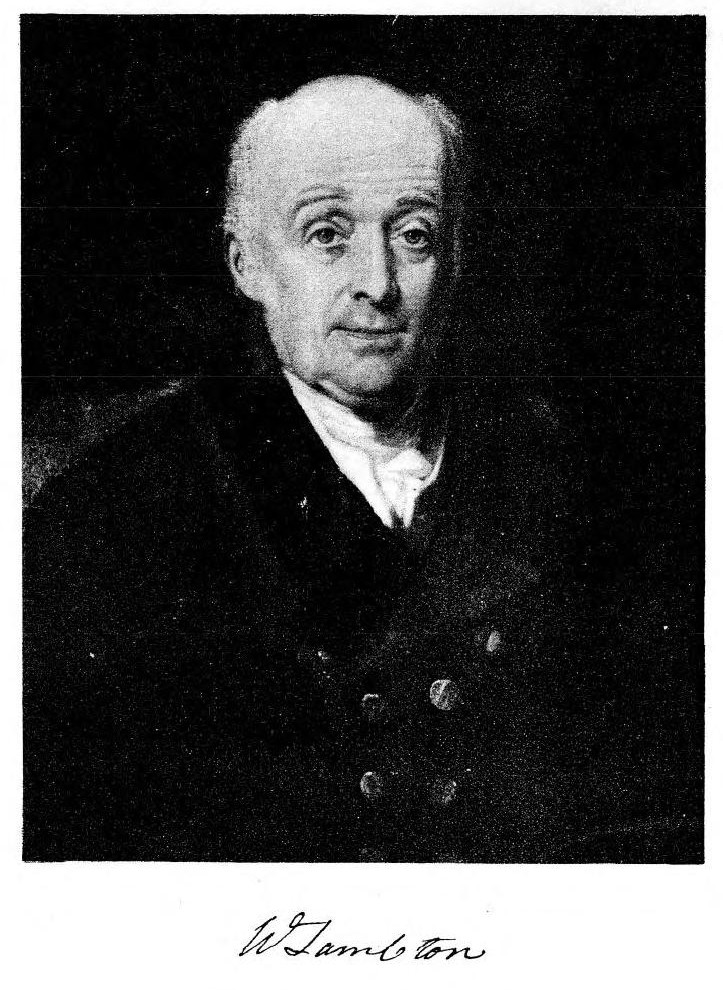

William Lambton

Source: WIkipedia

William Lambton was born into a farmer’s family in northern England in 1753, and enlisted in the army as an officer. His exceptional skills in mathematics led him to be assigned to measure land for English settlers in America. He fought on the side of the British during the American War of Independence, and was taken prisoner at the Battle of Yorktown in 1781, the last major land battle in the war. Subsequently he was posted to India where he fought in the Anglo-Mysore wars.

After the capture of Mysore, Lambton proposed that the territory be surveyed using the techniques of geodesy employed by William Roy in Britain. This proposal was nearly shot down by a major-general who declared it unnecessary as a topographical survey was already being undertaken by Col Colin Mackenzie. The proposal was, however, examined by the Astronomer Royal in London, who saw the scientific value in Lambton’s proposed survey and gave his support to the project.

He began his survey from St. Thomas Mount in Madras in 1802, and having covered the southern part of India, started to proceed northwards until his death in 1823 in Hinganghat near Nagpur – where he lies buried today.

Source: Sandes, E W C (1935) Military engineer in India. Vol. II

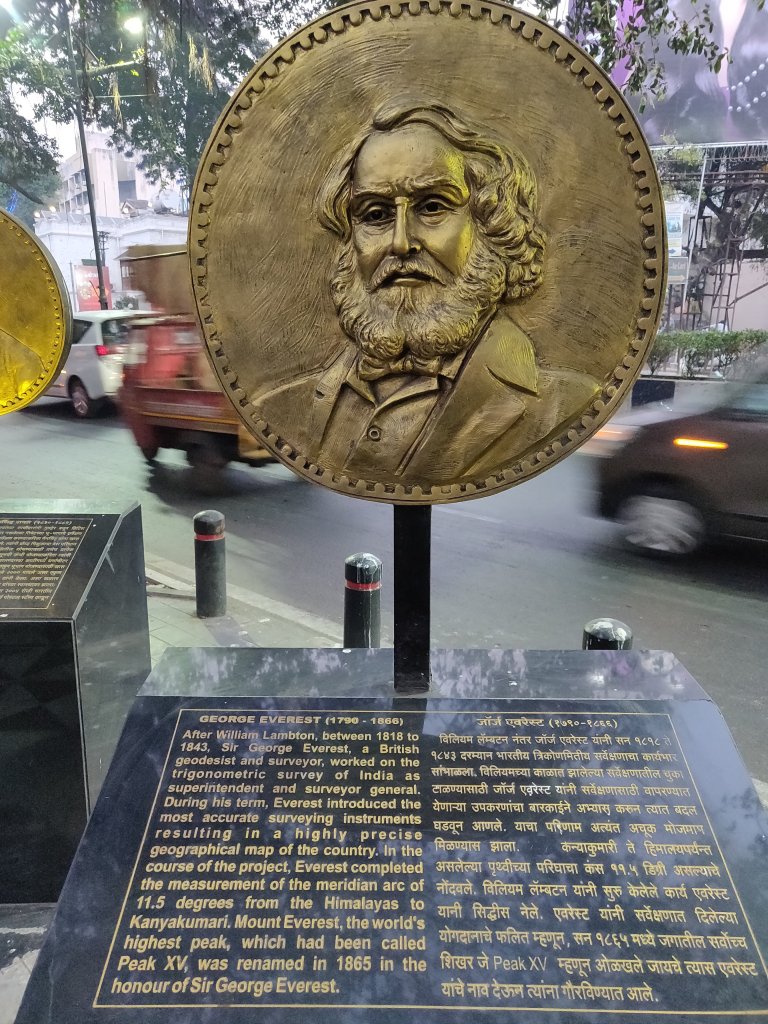

George Everest

Photo: Maull & Polyblank Studio

Born into a wealthy family in Britain, George Everest got commissioned into the Bengal Artillery at the age of 26 after completing military training at Sandhurst and Woolwich, and set sail for India in 1806. He was briefly sent to Java where he was asked to survey the island. On returning, he surveyed a semaphore line (a line of stations, typically towers, for the purpose of conveying textual information by means of visual signals and flags) from Calcutta to Benares. His work was noticed by William Lambton, who decided to appoint Everest as his Chief Assistant.

After Lambton’s death in 1823, Everest became the Superintendent of the Great Trigonometrical Survey, and was appointed the Surveyor-General of India in 1830. The arc from Cape Comorin to the northern part of the Company’s territory in India was completed in 1841 under his tenure, under the supervision of his protege, Andrew Waugh. The Company had provisionally appointed a man named Thomas Jervis as his successor – who subsequently delivered a series of lectures to the Royal Society in London on the perceived deficiencies of Everest’s methods. In response, Everest wrote a series of open letters to the President of the society in which he criticised the society ‘for meddling in matters of which they know little’. Jervis withdrew from consideration, and Everest successfully secured the appointment of Waugh, with whom he had an excellent relationship, as his successor.

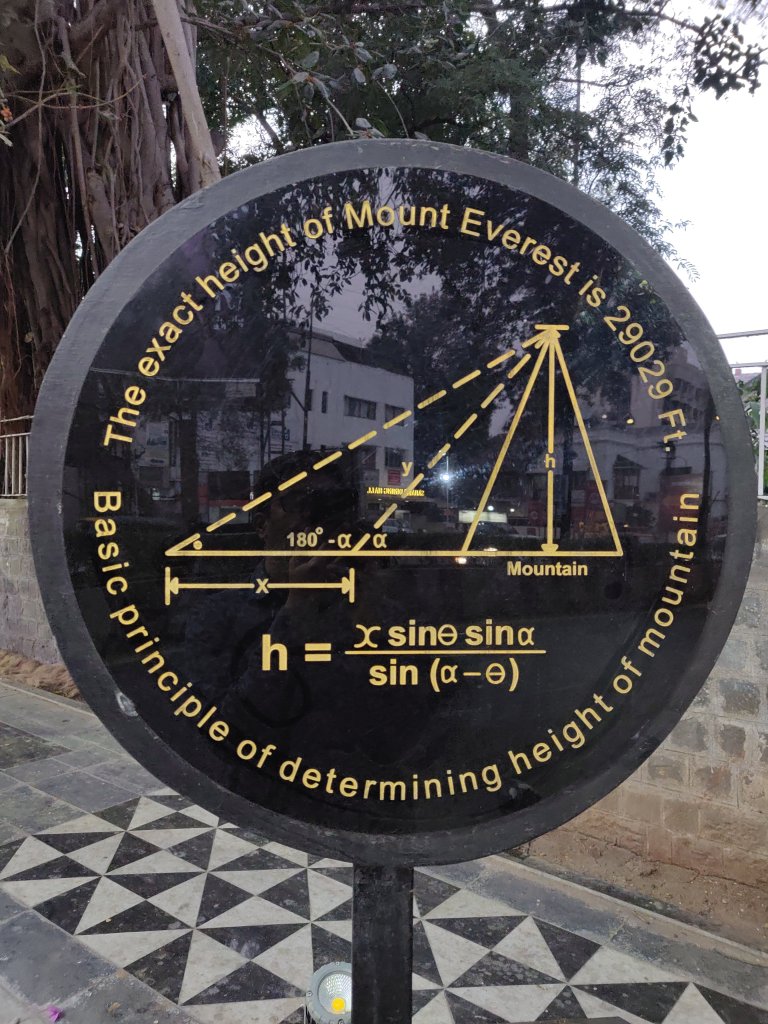

Andrew Waugh and the Story Behind Mount Everest’s Name and Height

In 1843, Everest retired, and Waugh was appointed the Surveyor-General of India. Waugh’s tenure involved primarily surveying the Himalayan region. In an era before calculators, it took months for a team of people to calculate, analyse and extrapolate the trigonometry involved. According to accounts, it was in 1852 when Radhanath Sikdar, an Indian mathematician came to Waugh to announce that what they had labelled as Peak XV was the highest point in the region, and perhaps, in the world.

To ensure that there was no error, Waugh took his time and did not publish this result until 1856. When Everest was at the helm of affairs, the Survey tried to preserve local names if possible, such as Kanchenjunga and Dhaulagiri, but in some cases, they couldn’t find a commonly used local name. This search was made tougher due to exclusion of foreigners in the kingdoms of Nepal and Tibet. Sometimes, there were multiple local names, and they found it difficult to favour one name over all others. Andrew Waugh, then-Superintendant of the Survey, proposed that Peak XV be named after his predecessor – George Everest. George Everest himself opposed this selection, arguing in 1857 that ‘Everest’ would be difficult to write in local languages and pronounced by “the native of India”. However, Waugh’s proposed name prevailed in spite of Everest’s objections, and in 1865, the Royal Geographic Society officially adopted Mount Everest as the name for the tallest mountain peak in the world.

Fortuitously, George Everest wasn’t very far from the truth in his concerns about pronunciation, as the mountain came to be pronounced universally (not merely by “the native of India”) as “Ever-est” and not “Eve-rest”, as he pronounced his own name.

Interestingly, the height of Mount Everest was calculated to be exactly 29,000 ft (8,839.2 m) high, but was publicly declared to be 29,002 ft (8,839.8 m) in order to avoid the impression that an exact height of 29,000 feet (8,839.2 m) was nothing more than a rounded estimate. Waugh is therefore wittily credited with being “the first person to put two feet on top of Mount Everest,” though Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay might disagree!

Waugh was succeeded by James Walker, who completed the Great Trigonometric Survey of India.

Radhanath Sikdar

If we credit the British for initiating the mapping of the subcontinent, it was mostly Indians who worked behind the scenes, in an astonishing variety of roles. One such man was Radhanath Sikdar.

In 1831, George Everest was looking for a young mathematician with proficiency in spherical trigonometry, when a mathematics teacher at Hindu College, Calcutta (later Presidency College and Presidency University), recommended his student Radhanath Sikdar, only 19 years old then. Sikdar joined the Survey as a “computer” in 1831, and his contributions to the Survey were enormous.

After being stationed in Sironj near Dehradun for twenty years, he was transferred to Calcutta in 1851 as the Chief Computer. While he was here, he also served as the Superintendent of the Meteorological Department, in addition to his duties at the Great Trigonometrical Survey. While working at the Met Dept, he introduced several innovations that soon became standard procedures for many decades. The most notable of these was the formula for conversion of barometric readings taken at different temperatures to 0 degrees Celcius.

While he was deeply venerated for his mathematical abilities, he didn’t always get along very well with the colonial administrators. He was a man who wasn’t afraid of standing up for his countrymen. In 1843, he protested against the exploitation of survey department workers by a British Magistrate, and in 1854, he, along with his friend Peary Chand Mitra, founded the monthly Bengali journal Masik Patrika, regularly writing for it.

He retired from service in 1862, and went on to teach mathematics at Duff College (now Scottish Church College) in Calcutta for a few years before his death in 1870.

After his death, the Survey Manual, which was one of the biggest publications for surveyors around the world, removed Sikdar’s name from its contributors in its third edition, after his death, in spite of him having written the more technical and mathematical chapters of the Manual. The incident was condemned by many British and Indian publications, with the paper Friend of India calling it ‘robbery of the dead’.

Photo: Pavel Novak.

Nain Singh Rawat

Saving, in my opinion, the best for the last, out of all the contributors to the Great Trigonometrical Survey, the one I find most fascinating is without a doubt Nain Singh Rawat.

Rawat was born in 1830 in the Kumaon region of Uttarakhand, close to the Indo-Tibet border. After leaving school, he helped his father with his work, and travelled to Tibet with him, learning the Tibetan language, customs and manners. Owing to similarities in appearance and culture, many people in the border areas would frequently travel to markets in Tibet, a country which was otherwise closed to foreigners.

In 1855, he was recruited by a team of German geographers who had approached the office of the Survey and arranged for permission to conduct a survey of their own. During this trip, he travelled by foot across Tibet to lakes Mansarovar and Rakas Tal, and then further onwards to Gartok and Ladakh. Since he was fluent in Tibetan language and culture, it was easy for him to blend in and not attract attention.

After returning from the expedition, he served as the Headmaster of a small primary school in his village for five years, before being selected to join the Great Trigonometical Survey in 1863, where he was trained in navigation and espionage.

Disguised as a Tibetan monk, he walked from his village in the Kumaon region through Nepal and Tibet to places as far as Kathmandu, Lhasa and Tawang (in today’s Arunachal Pradesh).

The part that blows my mind every time I think about it, is that he was trained to walk at a perfectly calibrated pace covering one mile in precisely two-thousand steps, which he would keep count of using a Buddhist rosary!

His second voyage in 1867 involved exploration of Western Tibet, and the final voyage in 1873 (after the completion of the Survey) was from Leh, Ladakh to Lhasa, Tibet, a much more northerly route than his previous expeditions.

In recognition for his feats as an explorer, he was presented with an inscribed gold chronometer by the Royal Geographic Society in 1868. According to Col Henry Yule, a Scottish geographer who spent much of his life studying India, “his explorations had added a larger amount of important knowledge to the map of Asia than any other living man”. He was also awarded the Victoria or Patron’s Medal of the Royal Geographic Society, an inscribed watch of the Society of Geographers of Paris, and a land grant of two villages by the British government in India.

Coming Back to Pune

It’s January 2020, and I’m back in Pune for a mini-holiday. Walking down the Sadhu Vaswani Path from Ohel David Synagogue towards the railway station, I stumble upon the same site where the Zero Stone was located, and to my surprise – the entire pavement had been redesigned and, in a wonderful example of thoughtful streetscaping, now featured a memorial to the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India.

I have no idea why the couple in the picture is facing the other way though.

But what happened to the zero stone, you ask? It’s still there, since 1872, although now the text has been painted golden, and with a memorial right next to it, I’m sure it turns a lot more eyeballs and finds its way into a lot more Instagram stories and blog posts today than it did earlier.

I sincerely hope it is never removed.

I hope you enjoyed reading this post. If you wish to see the zero stone of Pune for yourself, it’s located at Sadhu Vaswani Path, right outside the Pune General Post Office.

26 replies on “The Zero Stones of Pune and London; and Measuring the Whole Subcontinent”

Love anything related to documentation. Having done some triangulation myself, its mind-blowing how something like that was carried out for the subcontinent. Wonderful piece!

LikeLike

Thank you so much, Simran. I’m so glad you liked it! 🙂

LikeLike

Such a well researched article! Learnt a lot. Loved it!

Thank you, Anmol!

LikeLike

Thank you Rajenki, I’m glad you liked it 🙂

LikeLike

Very well written. There is a similar point in Nagpur called centre point which is supposed to be the centre of India. It’s quite hidden and one tends to just go past it without a thought!

LikeLike

Exceptionally well written!! What’s not to like about this?? History, Geography, Maps, London, Pune & intriguing bits for future blogs. Awesome. Take a bow Anmol!!!

LikeLike

Thank you so much, sir. I’m truly glad you liked it! Will write more and share with you.

LikeLike

Loved it…. These little pieces of street history are evocative indeed. Remember reading in Nat Geo about manhole covers in NY that were cast in foundries of Howrah, WB.

LikeLike

Thank you so much, uncle. Glad you liked it.

LikeLike

This is great Anmol! I’ve lived many years in Pune over the last 26 years but never looked for such trivia! Thank you regards Anurag Sharma

LikeLike

Thank you so much. I’ve written another article on two synagogues in Pune that I think you might like. It’s here on this blog itself. Please check it out. 🙂

LikeLike

What a well researched post! On such an esoteric topic! Loved it

LikeLike

Terrific piece Anmol.

Read it.And then reread it,just to fully absorb all those delicious bits of trivia scattered all across the piece.

And loved your writing style too.

This could easily pass off as a piece in one of the Sunday magazines that come with newspapers and I wouldn’t be surprised.

Few people who can mash history, trivia and travel so well.

Keep at it. I’ll be a regular reader for sure. 👏

LikeLike

Thank you so much, sir! Will definitely write more and share with you. 🙂

LikeLike

Thoroughly enjoyed reading it. So proud of you. Keep up the good work and sky is the limit. God bless!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you 🙂

LikeLike

Lovely awesome

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much 🙂

LikeLike

Hi Anmol am a Y batcher. Waiting for your next post.

LikeLike

WOW! That’s a lot of history. Even after staying in Pune, I never got a chance to spot the Zero Stone. Very well written, Anmol.

https://nanchi.blog/

LikeLike

Thank you so much, I’m glad you liked it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! Never knew there was so much history behind such an innocuous looking piece of rock. Thank you for bringing out the story so lucidly in your inimitable style. The good thing is the recognition given to it and to the historical figures behind it

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very well researched and explained.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is so engrossing ! I am reading it again right away.

History is so engaging and you are a storyteller par excellence!

Keep them coming Anmol.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much! I’m so glad you are enjoying the articles!

LikeLike

I thoroughly enjoyed this post. Thank you for your research.

LikeLike